Recently, the New York Times released an interactive version of the game Rock Paper Scissors.

RPS is essentially a break-even game. By playing Rocks, Paper, or Scissors randomly, one is guaranteed on average to win as often as one’s opponent. Therefore, the only type advantage that one player can have over another would be psychological. In essence, can beat a human opponent by taking advantage of people’s poor ability to generate random numbers. A person, in attempting to be random, or even in an attempt ing to gain a psychological advantage, may fall into patterns that can be exploited.

The New York Times’ website designed such a program to exploit these tendencies in human opponents. The designers of the Times’ interactive game claim to use the past history of a person’s moves to anticipate and counter that individual's next move. The article explained in general how this works. The opponent computer algorithm builds up in memory a string of a person’s move history as he plays the game. It then searches through the person’s last few moves and looks for a matching pattern earlier in the game. Based on what the person did after that earlier matching patter, the computer guesses what the person will do as his next move.

For example, let’s say that after 10 games a person’s history looked like RRSRPSRSRP. The last three moves that this person made were “SRP”. The algorithm would look through his history for another time that he threw “SRP” in that order: RRSRPSRSRP. Beginning at the third move, the person threw “SRP” followed by an “S.” Therefore, the algorithm would guess that the person is again going to throw an S and, to exploit this potential pattern, the computer would counter with a R (since Rock beats Scissors). The algorithm starts by looking for long strings 5 moves long and then searches for shorter strings if no longer string patterns are matched.

I've coded up my version of the game, which can be played here (and the code can be viewed here.

This algorithm is pretty simple, but apparently somewhat effective. However, since it’s a fixed algorithm, it’s perfectly exploitable. Simply put, if one were able to perfectly recreate the algorithm based one ones own moves, one could predict the computer’s guess for the human’s move. With this guess, one knows what the computer will throw, and therefore one can simply throw the hand that beat’s the computer’s move. It’s simple and quite insidious. So, I set out to do just that. I wrote a short python script that, as best as it was described by the Times, copies the Times’ algorithm. By knowing the algorithm, I can do my best to beat the machine at it’s own game. If the computer thinks that I’ll throw a Rock, it will throw a Paper. But if I know that the computer think I’ll throw a Rock, I know it’ll throw a paper, and instead I can throw a Scissors.

My Code: RocksPaper

I’ve included my python code and an example of how to run it. I chose python because itsinteractive interpreter allows me to use the code to in real time play against the computer. An example of a round I played is as follows: After the 8th round:

Game.playNext()

Throws so far: ['R', 'R', 'P', 'S', 'S', 'R', 'S', 'S']

Last 4 : ['S', 'R', 'S', 'S']

Matching Plays: []

Last 3 : ['R', 'S', 'S']

Matching Plays: []

Last 2 : ['S', 'S']

Matching Plays: ['R']

Suggested Play: S

As you can see, MY algorithm started by looking at my last 4 throws and seeing if there were any such throws in my history. It found none, and then moved on to 3 and finally 2. My last two throws were “S,S”. My code found that I had previously thrown SS starting on the 4th round, and after that pair, I had thrown a R. The Times’ program, based on that, would anticipate that I would throw a R, so it throws a P. But since I know it’s going to throw a P, I throw a S.

Using this strategy, I overwhelmingly defeated the computer. It was pretty satisfying, actually. I felt a little bad seeing the computer be so wrong so often. But I realized that I was simply doing what the computer was attempting to do to me. The algorithm was attempting to understand the complexities of human psychology and use them against us. I was simply using the simplicity of the computer’s psychology against it.

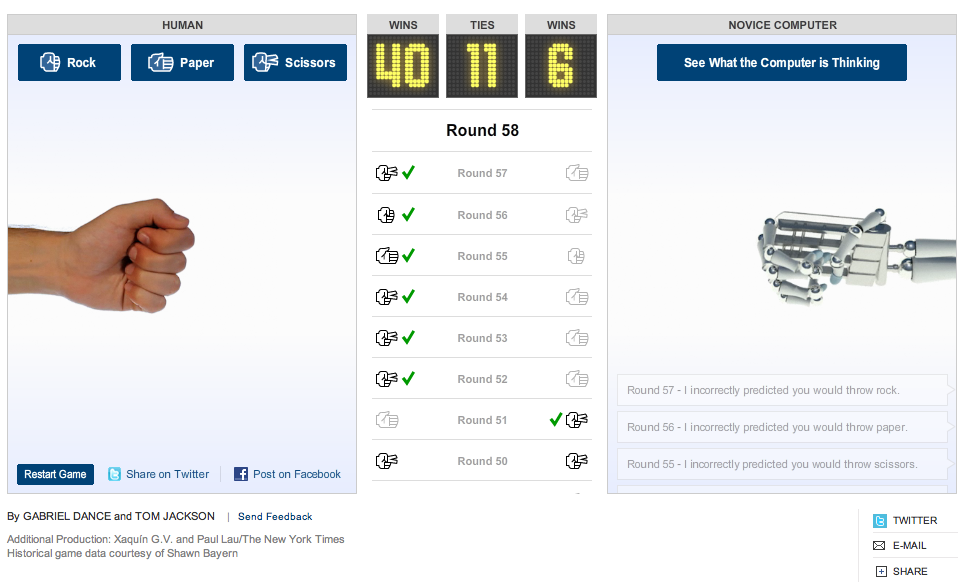

After 57 games (when I arbitrarily stopped playing), I had amassed 40 wins to the computer’s 6, with 11 ties.

As the complete nerd that I am, I wanted to quantify my victory, so I decided to compare that level of victory to the amount of victories that one would expect using a random-only strategy. In Stat-speak, I wanted to calculate the p-value of a random RPS strategy.

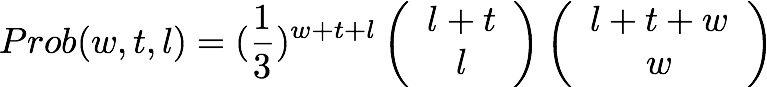

It’s easy to show that the probability of a particular end-game result of W wins, T ties, and L loses (ignoring order, which isn’t important) is given by:

(The brackets indicate the binomial, or "choose," function).

One can then simply preform a sum to calculate the total probability of obtaining as many or more wins minus losses from random chance. Using my numbers, I calculate that the chance of a random strategy doing as well or better as my strategy is 9.26 * 10 ^ -9. This is certainly a statistically significant result (it’s better than the 5 sigma significance required by higher energy physics, which corresponds to a p value of 5.7 * 10^-7. My value falls somewhere between 5 and 6 sigma.)

Though the problem is pretty trivial in terms of computer science, I’m glad that the NYTimes made this demonstration. I imagine that the authors of this program were inspired to the success of Watson in playing Jeopardy. I think it’s a good thing that the Times is seeking to demonstrate how powerful even very simple computer algorithms can be. And it was certainly a fun exercise to try to beat the Times’ model. If I were making my own model, I would make a few changes (for example, I would consider simultaneously the result of different size string searches). But the point wasn’t to make the best possible computer RPS player. Rather, it was to encourage people to think algorithmically and to elucidate how programmers approach computer challenges.